Programming Beats 2: Linear Drumming

Problem:

Your programmed drum beats tend to use the available instruments in “expected” ways: Hi-hats keep time, kick drums emphasize the beats, snares/claps are placed on or around the backbeats (beats 2 and 4). But in the music you admire, you sometimes hear other, more creative ways of working with drums. Sometimes it almost sounds like the drums are playing a “melody” of their own. But when you try to create patterns like this, it just sounds random and chaotic.

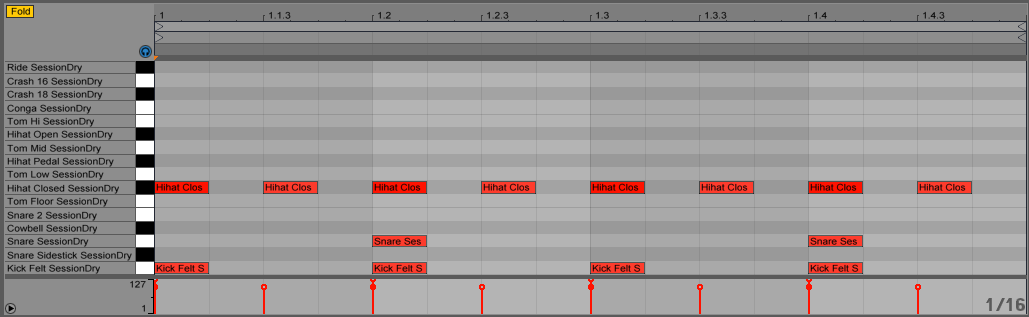

The various instruments in a drum kit have a tendency to be used in a somewhat standardized way. This is true across a variety of genres, both acoustic and electronic. For example, here’s a very basic rock and roll drum pattern:

The kick drum plays on every beat, the snare on the backbeats, and the hi-hats on every eighth note.

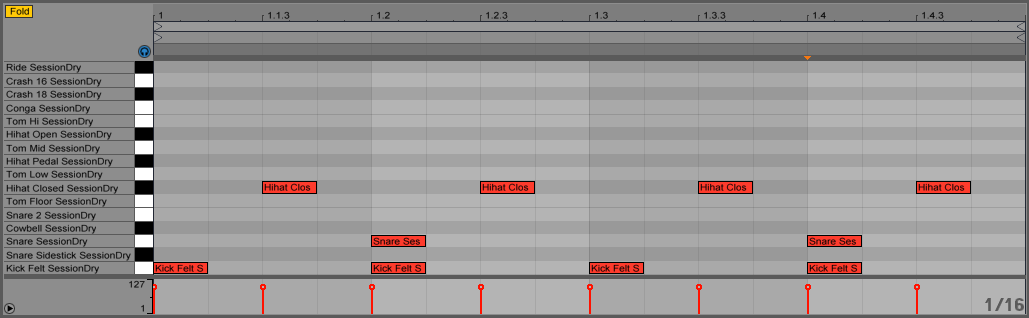

This can be converted into a very basic house pattern simply by removing all of the hi-hat notes that appear on strong beats (leaving only the offbeat eighth notes):

One of the hallmarks of these kinds of conventional drum patterns is that they’re polyphonic—multiple instruments can play at the same time. For a human drummer with four limbs, there’s a maximum possible polyphony of four simultaneous “voices.” Of course in the electronic realm, there’s no such limitation, although experienced drum programmers who are working in styles that are meant to mimic acoustic drums will generally stick with this four-voice limitation in order to create parts that sound as realistic as possible.

A side effect of thinking about drum patterns as polyphonic textures is that we tend to treat at least one layer as unvarying. In the grooves discussed earlier, for example, note that each individual instrument maintains a symmetrical pattern that never changes. In many musical contexts, these kinds of simple, steady patterns are completely appropriate. But here’s another way of writing drum patterns that can yield some interesting results.

Solution:

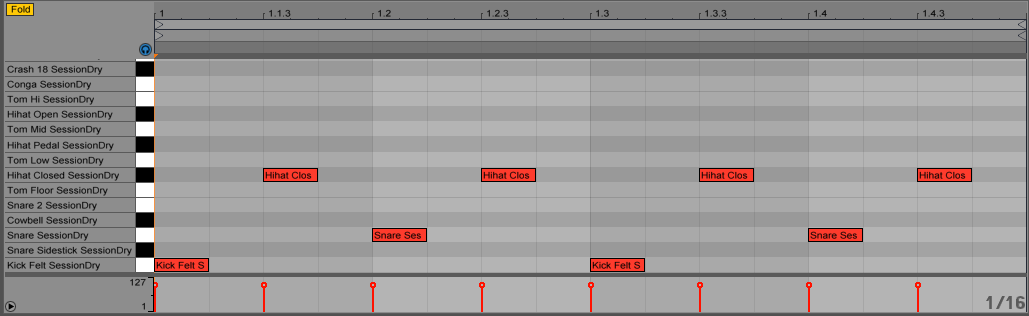

Acoustic drummers (particularly in some funk, R&B, and fusion contexts) sometimes use a type of playing called linear drumming. This simply means monophonic—no two instruments can play at the same time. Linear drumming is similar to the melodic technique called hocket (see Linear Rhythm in Melodies). An extremely simple linear drumming pattern derived from the previous examples might look like this:

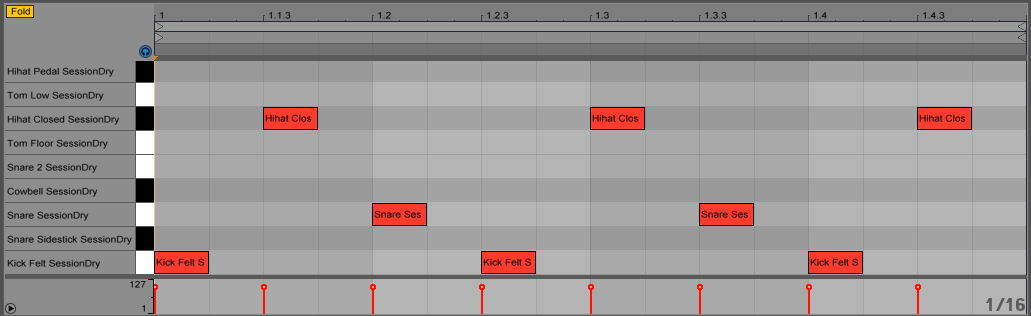

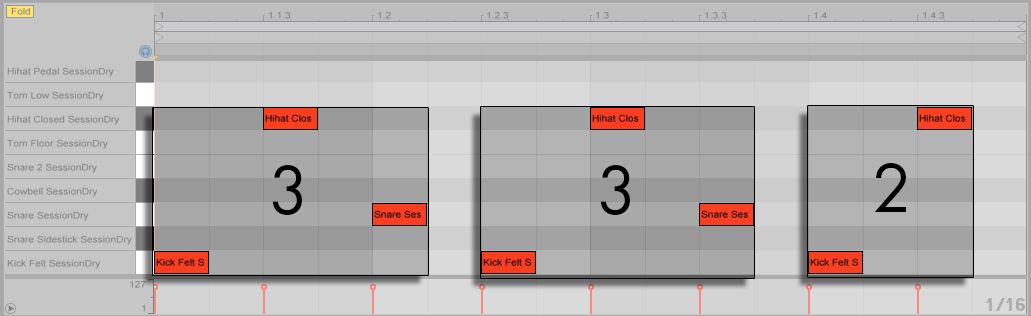

But rather than just taking a conventional pattern and removing overlapping elements, try thinking about how to use the monophonic requirement in creative ways. For example, treating a monophonic drum part as a single, quasi-melodic line of notes may cause you to think of each instrument as having the same level of importance, rather than subconsciously assigning them to functional roles (like “timekeeping” or “accenting”). Consider the following pattern:

In the above pattern, sub-patterns in groups of three notes play against the expected flow of time, before “correcting” with a two-note pattern at the end of the measure.

These types of unusual note groupings treat each instrument as equally weighted, rather than using the overlaying of multiple voices to emphasize particular beat positions. Interestingly, patterns like this tend to be perceived very differently at different tempos. At a fast tempo such as 170 bpm, this pattern takes on a “rolling” character, and the composite line—the perceived fusing of the separate parts— becomes much more audible in relation to the individual notes. Linear patterns like this are common in drum and bass grooves, for example.

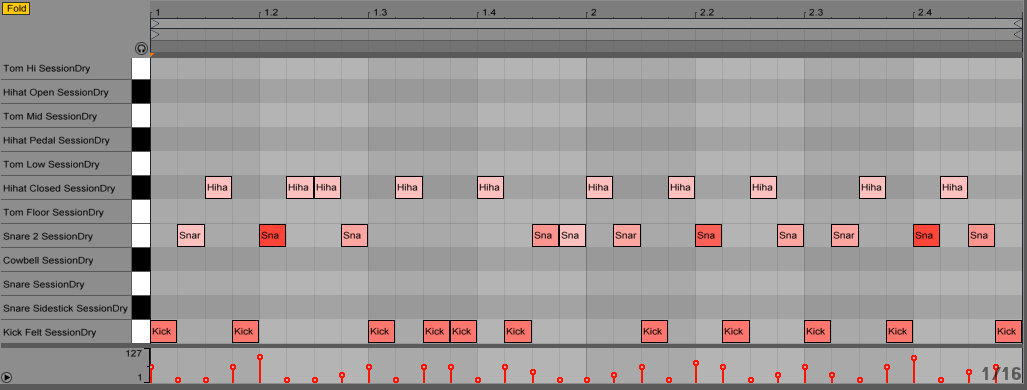

It’s also potentially interesting to add an additional level of restriction. You might decide, for example, that your pattern will be based entirely on sixteenth notes, and that every sixteenth-note position on the grid must contain a note. A complex two-measure version of such a pattern might look like this:

As with the previous pattern, the linear approach here helps to “democratize” the instruments. No one voice has dominance over the others, and the traditional roles of timekeeping elements vs. accenting element are eliminated. Also, notice that there’s a lot of variation in note velocities in this example. Just by changing the volume of certain notes in relation to the others, you can make a single pattern of notes take on an entirely different character.

Linear drum patterns aren’t right for every musical context, but they can offer a different way of thinking about beat programming that may help you come up with new patterns and variations that you might otherwise not have considered. And of course, as with all of the suggestions in this book, there’s no reason to restrict yourself to strictly following the monophonic requirement. If a linear pattern would sound better with some instances of multiple simultaneous voices, go ahead and use them.