Arranging as a Subtractive Process

Problem:

You have more than enough ideas to make up a finished song but don’t know how to actually put the arrangement together. Even the process of arranging sounds like an intimidating commitment. How can you even begin, let alone finish?

In the context of music creation in a DAW, the arrangement refers to the layout of the parts of your song along a timeline. You may have assembled a rich pool of material, but the actual act of putting that material in some kind of order that unfolds over time is what will eventually turn that material into a finished song.

Getting from “pile of stuff” to “song” is a difficult process, both conceptually and technically. The most common way people approach creating an arrangement is the most obvious one: Gradually fill the empty arrangement with various combinations of the material you’ve made, moving from left (the beginning) to right (the end). In this workflow, the arrangement timeline is analogous to a blank canvas to which you apply paint until a finished painting appears from what was originally empty, white space.

This process works, of course. But facing emptiness can be scary. Even though you’ve already put in a considerable amount of time preparing the materials that you plan to use, you now face something that might feel like a reset to zero. Beginnings are hard, and a blank canvas (or empty timeline) can be a difficult mental bridge to cross.

Solution:

If you’re finding that you’re stuck at the arranging stage, here’s one process that might help: Start by immediately filling your entire arrangement with material, on every track. Spend as little time as possible thinking about this step; the goal right now isn’t to try to create a good arrangement. You just want to start with something rather than nothing. It’s OK that you don’t know how long the song will eventually be. Just fill up an average song’s worth of time (or even more) in whatever way is the fastest for your particular DAW—by copy/ pasting blocks of clips over and over again, via a “duplicate” command, or (in some DAWs) by dragging the right edges of clips to extend them.

Perhaps you’ve already given some thought to how your material will be divided. Maybe you’ve named certain clips things like “Verse” and “Chorus” so that you can better organize them when arranging. Don’t worry about any of that for now. In fact, don’t even try to use all of the material you have. Just grab a pile of ideas from each track, and fill the empty space. This process should take no more than about 20 seconds. If you’re spending more time than this, it probably means you’re trying to make creative decisions. For example, maybe you’re thinking “I already know that this chunk of ideas will go before this chunk of ideas, so to save time later, I’ll just lay them out in that order now.” Resist the temptation to organize anything in this phase, and simply move as fast as possible.

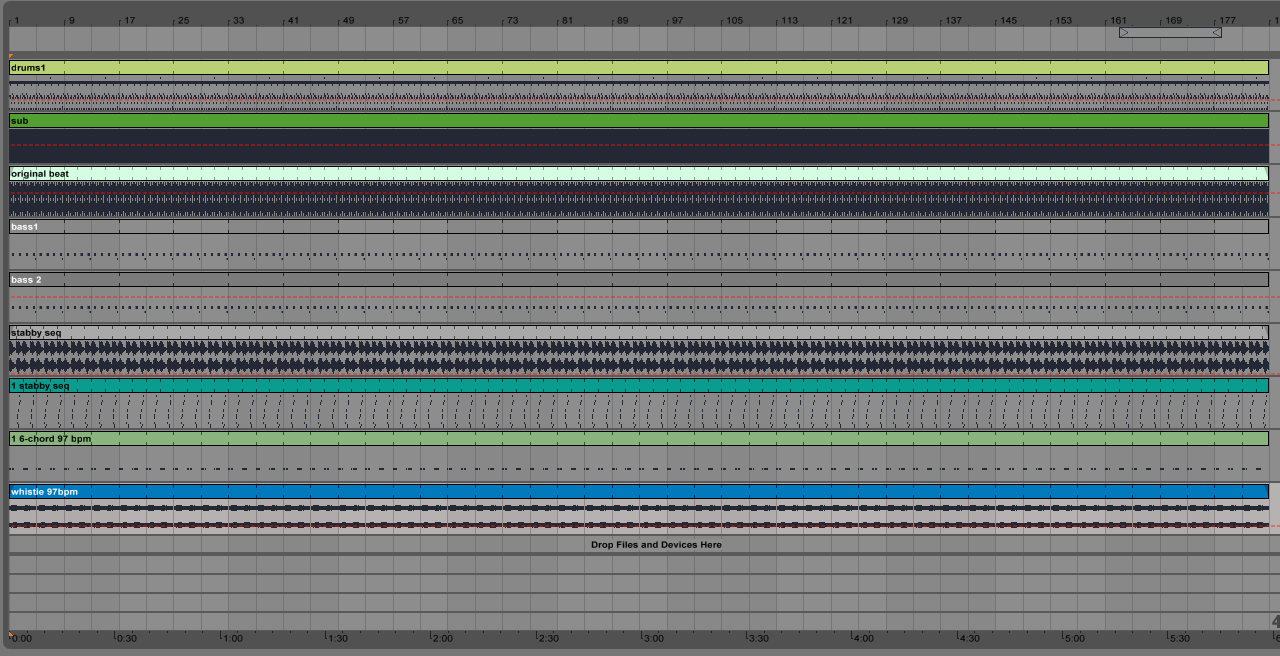

As an example, here’s a 6-minute arrangement timeline, filled as quickly as possible.

Now that you’ve filled the timeline, the process of actually making your arrangement into music becomes one of subtraction rather than addition. If the traditional arranging workflow is analogous to painting, the subtractive workflow is analogous to sculpting. You’re beginning with a solid block of raw material and then gradually chipping away at it, creating space where there used to be stuff, rather than filling space that used to be empty.

This can be a much more productive way to work for a number of reasons. For example, it’s often easier to hear when something is bad than it is to imagine something good. If a particular combination of ideas doesn’t make musical sense, you can generally feel this right away, and the steps to fix it may be obvious: Maybe an element is simply too loud, or the bass line clashes with the harmony. And because you’re listening back to an actual flow of sound over time, you’ll probably have an intuitive sense of when a song section has been going on for too long—your own taste will tell you that it’s time for a change.

If you’re working in a genre in which textural density tends to increase and decrease as the song progresses, you may already have your “thickest” sections of material finished at this point. You may find that you’re actually able to work backwards from the end of the song towards the beginning, removing more and more elements as you go back in time.

Bonus tip: Most DAWs provide a way to insert or delete chunks of empty time in the middle of an arrangement. When using a subtractive process, these tools can be extremely helpful. For example, you may have finished editing work on what you originally thought would be two adjacent sections of material, but then realized that something else should come in between, or that the first section needs to be twice as long. Inserting time in the middle automatically shifts everything after this point to the right, which is much faster and safer than trying to cut and paste many tracks’ worth of material manually. Or maybe you’ve realized that a section you’ve been editing is too long. If your DAW has it, use the delete time command to remove the excess material, which will cause everything to the right to automatically shift to the left to fill in the gap.