Creating Melodies 1: Contour

Problem:

When you listen to music that inspires you, the melodies are strong, memorable, and hummable. In contrast, your melodies feel weak, aimless, and wandering.

Writing a good melody is challenging. Here are some ideas for writing better melodies by thinking about their contour.

Solution

The term contour is used to refer to the shape of a melody over time— whether the notes rise to higher pitches, fall to lower ones, remain at the same pitch, or some combination of these. Additionally, we use contour to discuss whether a melody moves by adjacent notes (known as conjunct motion or motion by step) or by larger intervals (known as disjunct motion or motion by leap).

A few general rules:

- Good melodies have a strong sense of balance between both aspects of contour: rise vs. fall and conjunct motion vs. disjunct motion. For example, if a melody rises for a while, it might make sense for it to then fall by roughly the same amount.

- If a melody has moved by step for a while, a good choice might be to then proceed by leap in the opposite direction. The converse also applies: Commonly, a melody that has moved by leap will then move by step in the opposite direction. One situation in which this might not be necessary is when a melody is simply an arpeggiation of a chord in the harmony. In these cases, the leaps between chord tones may sound “complete” even without stepwise resolution in the opposite direction.

- Good melodies often have a single peak note. That is, the highest pitch in the melody occurs only once. Furthermore, that peak note often (although certainly not always) occurs on a “strong” beat. (Assuming a 4/4 meter, the first and third beats are considered “strong” or “on” beats while the second and fourth are considered “weak” or “off” beats. As you subdivide beats into shorter note values such as eighths and sixteenths, the same rule applies. That is, the odd-numbered subdivisions are perceived as stronger than the even-numbered ones.)

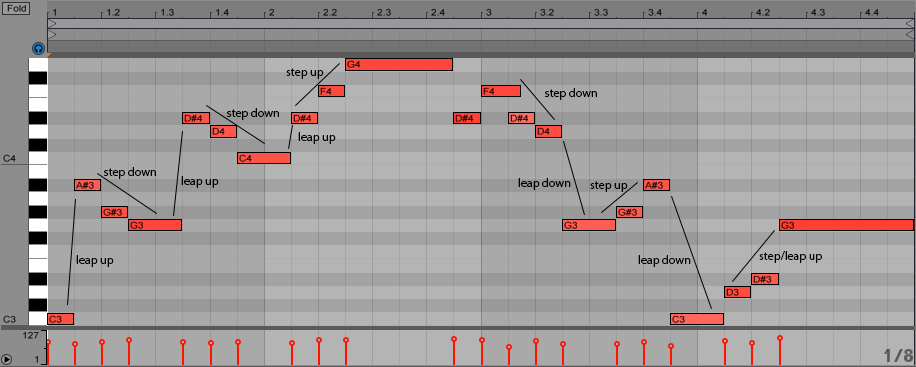

Let’s consider an example of a melody that (mostly) follows these rules:

The melody opens with a large leap up, which is immediately followed by two notes that step down. This pattern is then repeated in the next passage. Following this, we “break” the rules briefly to reach the peak note: A leap up is followed by two steps up. The second half of the melody also strays a bit more from the rules. Bar 3 begins with a descending stepwise figure which is then followed by a leap in the same direction. Next, we step up, and then leap down. The final gesture breaks the rules once again: We step up and then continue upward by leap to the last note.

The general contour of the melody is a kind of arc: We start from the lowest note in the passage and climb gradually to the highest note at roughly the halfway point of the melody, before gradually descending again to cover roughly the same amount of space in the second half.

As you listen to other melodies with contour in mind, you’ll find that most (including the one discussed earlier) don’t follow these guidelines 100 percent of the time. But in general, you’ll find that the contour of most good melodies maintains a balance between ascent and descent and stepwise and leapwise motion.